Testing software in the era of coding agents

What parts of my software should be tested? And how? And how do coding agents (e.g. Claude Code) change things? This is my attempt to succinctly explain how I think about these questions at the beginning of 2026 (software development is changing so quickly I feel compelled to note the date. This may all be obsolete soon).

Static analysis ⊂ testing

For the purposes of this discussion, I’m going to include static analysis in the term “testing” for brevity rather than writing “testing and static analysis”. Static analysis includes any checks that don’t have to execute the code, including the checks performed by compilers and linters.

Why test software

If it’s not tested, you have much less evidence that it works, where “it” is any particular combination of code, inputs, runtime environment, and assertions. So to the extent you care about the software working, you should test it.

Most software is tested manually when it’s first created. What’s wrong with manual testing? First, it’s slow! While the time cost of all testing grows with the number of changes being tested and the number of checks, the slope of the curve matters. Automated tests have a higher up-front cost of writing the test, but then a drastically lower marginal cost each time they’re run. The cheaper and faster the tests are, the faster one can make changes (while maintaining the same confidence in correctness).

The above was true before coding agents, but with coding agents, there are a few additional important considerations. First, the human time needed to actually write code is falling quickly (because you can have coding agents do it), but if checking correctness is slow (e.g. requires manual testing), that will become the bottleneck. Second, coding agents have a much higher chance of success if they can get quick feedback while they work. Third, manual tests often require more interpretation to determine if the system is working as intended, which is error-prone. This is especially true for coding agents that lack broader context and are somewhat prone to reward hacking. Agents are much less likely to misinterpret an assertion failure than something less well defined, and reward hacking is much more visible if it shows up as disabling an assertion in code rather than an optimistic interpretation of a manual test result.

How much to invest in testing

There are two main things that determine how much it makes sense to invest in testing. First, how much does it matter that the system is correct (or performant)? At one extreme we have code that only needs to work well enough to explore an idea (e.g., for learning about an algorithm). Investing a lot in automated testing for this type of thing is wasteful. At the other extreme is code that is doing critical work everywhere for everyone (e.g., OpenSSL).

Second, how often is the code or inputs or environment changing? If the rate of change is low, the total cost of manual testing is low. If the code is changed frequently (including changes to its dependencies), manual testing is wasteful. As software systems get larger, they typically accrue more interdependencies between modules, which greatly amplifies the effective change rate.

How to invest your testing budget

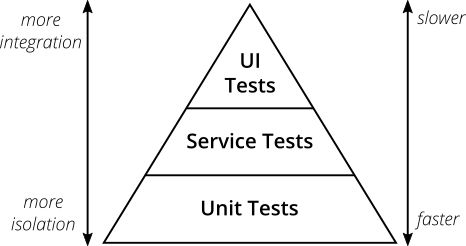

Build a test pyramid! Note the names of the layers probably don’t make sense, but in general you should have more isolated, fast tests, and fewer slow, integrated tests.

Quoting “The Practical Test Pyramid”: “Your best bet is to remember two things from Cohn’s original test pyramid:

- Write tests with different granularity

- The more high-level you get the fewer tests you should have

Stick to the pyramid shape to come up with a healthy, fast and maintainable test suite: Write lots of small and fast unit tests. Write some more coarse-grained tests and very few high-level tests that test your application from end to end.”

Again I think this becomes even more important with coding agents. They may have less of an understanding about which properties of the system are important and they will be much more productive if they can get feedback from static analysis tools or unit tests that are fast, specific, and not flaky.

How to integrate testing into the development process

When fixing bugs

A bug or performance problem is very strong evidence existing testing is insufficient! If you’re fixing a bug or performance regression, this is a great time to practice test-driven development by following these 3 steps:

- Write test. Verify it fails.

- Fix bug.

- Run test. Verify it passes.

This guarantees that you’ve actually understood and fixed the problem, and can help avoid regressions.

However, people frequently find it’s quite difficult to write tests that reproduce bugs or performance regressions. The code often needs to be refactored to make it easier to test. This brings us to…

When writing new code

If you’re writing new code that you expect to warrant testing (i.e. you care enough about the correctness or it’s going to be changed a lot), add tests from the beginning. This will naturally encourage you (or your AI agent) to design it in a way that makes it easy to test! You might find the “functional core, imperative shell” pattern useful here.

When refactoring

If you’re making a big change to the system that shouldn’t affect its output but you’re nervous and you feel like you should probably do a lot of manual testing to make sure, that’s a good sign that more automated tests may be needed.